Some call him the only avant-garde artist in Japan. Although fascinated with Picasso, he didn’t reject tradition, but did the opposite. He discovered the ‘original Japan’ for his compatriots: prehistoric art. Who was the creator of the Tower of the Sun, Tarō Okamoto? “Art is explosion!” Tarō Okamoto shouted in a TV commercial after striking a bell of his own design. Originally he had created it for a Buddhist temple. Each of the horns on the spiky bell bowl produced a different sound. Nowadays nobody remembers anymore what Okamoto was advertising, but Japanese people still associate him with this catchphrase.

“Art is explosion!” In fact, few artists would agree with these words, not to mention living and creating in accordance with it. Constant explosions are very difficult and exhausting for an artist. But each time I encounter Okamoto’s art, I have a feeling that some kind of eruption has just taken place. And as a result, new forms of life appear, which cannot be inscribed into any type of standing biological classification. When I look at them, they also show interest and assess with their eyes. Pretty much all of Okamoto’s sculptures – even though it would be difficult to call them figures – have faces, masks, sometimes even more than one.

Preschool level?

It was because of Tarō Okamoto that I lost trust in my guide to Japan, the Japanologist Alex Kerr. In his Lost Japan, recently published in Polish, he ridicules Okamoto for sculpting like a preschooler. A friend – supposedly quoted in passing – adds that he has never seen anything uglier than the Tower of the Sun. I felt the need to take one side in a clear way. I decided that Kerr, with his tempting reasoning, is simply – as futurists might say – a traditionalist glorifying the past. Is Japan even imaginable without Studio Ghibli, without colourful subcultures, without Hiroshi Yoshimura’s soundscapes and – well, exactly – without Tarō Okamoto’s art? I don’t even want to think what Kerr might say about Rei Kawakubo’s fashion.

Tarō Okamoto was the most important – some even say the only – Japanese avant-garde artist. He was quite lucky to go to Europe at the age of 18. He spent the 1930s in Paris, following the avant-garde movements. He was the youngest member of the Abstraction-Création group. He was noticed by André Breton, which was Okamoto’s chance to get closer to the surrealist circles. It was in Paris that he had his first revelation – when he encountered Pablo Picasso’s art. On the bus on his way back home from the Spaniard’s exhibition, he supposedly cried with excitement. He decided to go even deeper than Picasso.

The outbreak of World War II in Europe forced him to return to Japan, where he was enlisted and sent to the front in China. He struggled, being against the war. He was forced to paint portraits of officers. Upon his return to Japan, he found his family home burned down, together with all of his artistic output. He recreated some of his paintings, but had to start from scratch. He had to face the lack of understanding in the conservative society and artistic circles of Japan.

Towards the ‘original Japan’

He experienced another revelation in 1951, in a Tokyo museum. At an archaeological exhibition, he saw pottery from the Jōmon period, that is the Neolithic Age – the ancient times when the inhabitants of the Japanese islands were mainly hunter-gatherers. Their figurines and vessels, formed by hand, looked so otherworldly that Erich von Däniken could use them as yet further proof of our ancestors’ contact with extraterrestrial civilizations. Who left them here and why?, you could easily ask.

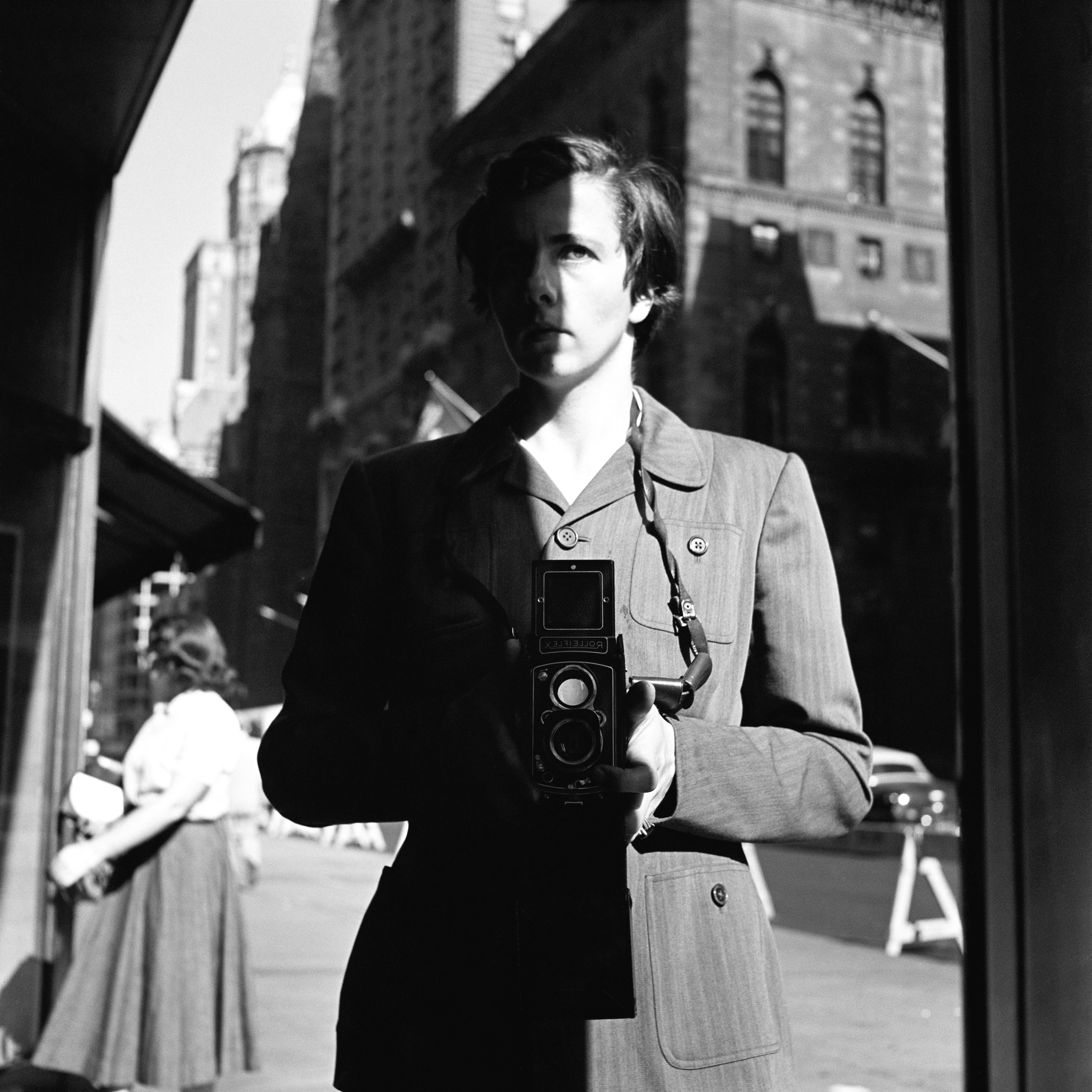

Already in Paris, Okamoto – on top of practising art – attended the lectures of Georges Bataille and the father of anthropology, Marcel Mauss. No wonder that – in contrast to some superficial opinions – Okamoto the avant-garde artist did not reject tradition at all. What’s more, he discovered the Jōmon pottery not just for himself. He photographed it, wrote about it and spread knowledge about it, like a professional anthropologist. First and foremost, he picked up on the energy of primitive civilization, a legacy that Japan should be particularly proud of.

The remnants of that culture encouraged Okamoto to continue on his own discovery of the mythical, ‘original Japan’, with trips to the furthest corners of the country. The longing for energy and beauty, which he had spotted earlier in the Jōmon pottery, led him to Okinawa and the Tōhoku region. He was fascinated with the rituals and shamanism still alive there, festivals and holidays rooted in the past. He was eager to participate in them. Ancient ceramics inspired Okamoto to reach for a medium new to him: sculpture. Through this expressive route, he was able to create his own reality. The more he worked, the further his imagination went in conquering new areas. He painted, sculpted, designed ceramics, and even drew on the night sky with helicopter lights. Like Picasso before him, he too – thanks to discovering Japanese tradition – created his own, unique, explosive language. That is why you can have the impression that Okamoto’s art is free of oriental clichés and based exclusively on his own personality.

Past anew

The breakthrough came at the end of the 1960s, when the organizers of Expo’70 in Osaka asked him to create a sculptural symbol for the first world fair in Japan. After the catastrophe of World War II, a huge effort was put into turning Japan into a modern state and Made in Japan labels finally started to be associated with products of the highest quality. The expo in Osaka was to celebrate this new face of the Land of the Cherry Blossoms, its contemporary technologies and – a year after the Americans had landed on the moon – its faith in progress. This expo was when IMAX films were seen for the first time, as well as mobile phones and maglev trains. After all, the theme of this huge endeavour was ‘Progress and Harmony for Mankind’. Which is probably why the organizers set their eyes on the only avant-garde Japanese artist. However, Okamoto’s attitude did not easily match these progressive slogans. He criticized the Expo’s message with the simple words: “It’s nonsense.” He was also not afraid to confront the world of great politics and architecture. Quite the opposite, in fact. He insisted that harmony emerges from confrontation. “We need to rediscover the past,” he said. In the middle of the exhibition, which looked like “the city of the future”, he proposed to erect a 70-metre tower that would pierce the futuristic roof, seemingly levitating over the main Expo plaza, designed by the head architect, Kenzō Tange.

Additionally, the tower was supposed to be slightly anthropomorphic and devoted to the sun. In one of the photos from the construction site, Okamoto makes crossed eyes and spreads his arms, imitating the gesture of the tower-sculpture behind him. Because the Tower of the Sun was a bit human, a bit totemic, a bit otherworldly. Two slightly raised arm-appendages grew from its sides. It had a few solar faces. The tower seemed to be unearthly, but, as Okamoto said himself, “the rarer something is, the more universal it becomes”. He managed to convince Kenzō Tange to approve his idea. In the spacious subterranean part of the sculpture, Okamoto put up an impressive exhibition devoted to life. An elevator could take a visitor to the very top of the tower, where the artist placed a colourful Tree of Life emerging from a primal soup and inhabited by numerous dinosaur species, showing the development of life on Earth. The ancestors of contemporary humans were placed on the highest branches. So it was also our genealogical tree. Okamoto wanted to show what we lose when we place too much trust in technological development.

The Tower of the Sun quickly became the symbol of Expo’70 and Osaka, but also of all of Japan. Overnight Okamoto was proclaimed the most loved artist in Japan. In the 1970s, his position was comparable to Yayoi Kusama’s today. This is probably why the decision was taken to keep the Tower of the Sun in place as one of the very few permanent remnants of the Expo. Recently, the Tree of Life was recreated and made available to visitors.

After the Expo, an avalanche of commissions came from various corners of Japan. Today, more than two decades after the artist’s death, you can travel around the islands following the trail of his sculptures. The most important points of the tour are of course the Tower of the Sun, the mural The Myth of Tomorrow, found years after its creation in Mexico and now displayed in Tokyo’s Shibuya station, the Okamoto Museum in Kawasaki, as well as his home and studio in Aoyama district, Tokyo.

His home – which is now a museum designed by Junzo Sakakura, Le Corbusier’s pupil, whom Okamoto met in Paris – shows the scope of the artist’s creation. There are piles of unfinished paintings in his old studio, his sculptures fight for attention. Everything here was designed by him – from plant pots to cups. The small garden is crowded with sculptures. Planters and seats turn into unidentified animals, white creatures with spiky protrusions peek from between banana leaves, expressing plant-like interests, as if aiming for the sun. You can even strike Okamoto’s spiky bell, the one from the commercial! And because everything here is equipped with eyes, you also feel watched. The real and the magical worlds mesh into one here. After all, “art is explosion!”

Translated from the Polish by Anna Błasiak